Peripheral Vision: Three Parks in Naples

“Toccammé!” — it’s my turn! — cried the child. He stood on the skateboard, completely still, arms outstretched like a surfer. “Mo’ me!” — Now me! — the next kid called out, taking the same stance. They swapped places over and over, and I stood in place, a bit dazed from the August heat, wondering how the skateboard was not moving every time they jumped into pose.

I had procrastinated as long as I could; it was time to climb the tufa cliff toward the main level of Ventaglieri Park. Looking at the two steep staircases, wondering which one to take, I was relieved to see an alternative: through a nondescript doorway cut into the wall, an escalator rose deep into the cliffside.

After several switchbacks of escalator runs, trying doors every few floors and finding them locked, I finally arrived at the top, at the gate of Parco Ventaglieri.

I had learned of this park, located near Montesanto station in Naples, a few days before on the website Il Verde A Napoli: I parchi della città, a brilliant collection organized by the city of Naples, with fact sheets on all of the parks in the city, each grouped by municipality. I scoured all the central districts for parks to visit, partly in my fascination with the design history of the city, and partly to find anything approximating shade to escape my non-air-conditioned apartment. I happened upon Parco Ventaglieri, the photos depicting angular brick planter beds, at turns classical yet also modern, and decided to visit.

Walking through the gate, I entered onto a narrow, sloped ramp descending into the center of the small park. Two terraced pergolas descended with me, parallel to the symmetrical ramped paths. In the remaining spaces left by the cuts of the paths were planting beds filled with white-flowered Oleander (Nerium oleander) and spindly Olive trees (Olea europaea). There were dozens of children running around, parents and elderly people sitting on benches watching them and chatting, and a group of teens huddled morosely on top of a split staircase leading to a shuttered section of the park. I was amazed at the liveliness of the space, especially for how compact it was.

Standing at the parapet, I was reminded of the great distance down to the lower portion of the park – with the soccer pitch painted with a graphic depiction of San Gennaro, the patron saint of Naples. A group of French teens were playing soccer, yelling and cheering. Along the west edge of the site, a high school with undulating roof terraces also matched the extreme topography of the hilly area.

Looking at the design of the school and how it interplayed with the park, and pondering other spaces I’d observed reminiscent of the same era, perhaps the 1980s, perhaps 90s, I started to have an inkling that there was something of a design renaissance in the city in this period. I was eager to find out more and to explore additional parks in Naples.

What I learned surprised me. Designed by Lucio Barbera, an architect and urban theorist who served as Dean of the School of Architecture at the University of Sapienza of Rome and later UNESCO Chair in Sustainable Urban Quality and Urban Culture, the Parco Ventaglieri complex was funded by something called the PSER program. And during this period, Barbera oversaw fifty other PSER projects across the city.

I realized this ‘renaissance’ was far more extensive than I had imagined. In the period of 1985-1995, twenty new parks were inaugurated in Naples, seventeen urban neighborhood parks and three major public parks of grand scale, all funded by the wave of PSER money that was released for redevelopment of the city following the Irpinia earthquake.

The Irpinia earthquake, the PSER program, and three parks on the Naples periphery

On November 23rd, 1980, a devastating earthquake centered in the province of Avellino, east of Naples, left 4,689 people dead and more than 400,000 homeless. This in turn created a severe housing crisis in Naples and the region, leading the Italian parliament to approve Law 219/1981, the Programma Straordinario di Edilizia Residenziale (PSER), which dedicated billions of lire to the construction of new housing and adjacent green/public spaces, and relaxed planning processes towards that end.

With the stated goal of creating 20,000 new residential buildings and accompanying green spaces, the Municipality of Naples, rather than starting the planning process from scratch, activated its Piano delle Periferie (Plan for the Periphery), which had just been approved in April 1980, only seven months before the earthquake. This allowed the immediate construction of housing and parks in the previously underserved outskirts of the city.

It was this work in the outer districts that really drew my attention. In addition to the 17 neighborhood parks, three major parks were constructed on a much larger scale and with a higher level of intervention. These three, Parco Massimo Troisi in the neighborhood of San Giovanni a Teduccio, Parco Fratelli de Filippo in Ponticelli, and Parco Ciro Esposito in Scampia, each had a surface area greater than 12 hectares/30 acres, making them the largest parks in the city, second only to former royal palace grounds. Additionally, the parks each showed a very intensive level of intervention: all three included earthworks of artificial hills rising high above the parks, and two featured man-made lakes with water surfaces over 8000 square meters, almost 2 acres each.

These were not historic royal palace sites repurposed for public enjoyment, nor central parks/villa comunali in the wealthiest districts of the city. Instead, they were built in three zones that, by the time the parks opened, had become some of the most degraded and troubled areas of the city. Visiting these spaces, I was overcome by their beauty and scale. It was clear that these works were truly unprecedented in 20th century Naples.

Three Parks in the Naples Periphery

Park 1: Parco Massimo Troisi

San Giovanni a Teduccio, Naples, Italy

12 hectares / 29.7 acres

Parco Massimo Troisi was constructed beginning in the mid-1980s and inaugurated in 1995. No designer is mentioned in any digitized archives I’ve found, and it’s assumed the design was done in-house by the municipal parks department. While the park could largely be characterized as ‘in ruins’, its framework, layout and architectural features remain evident, and I was very moved by their beauty. Many of the plant species are still extant, especially a wide diversity of now mature trees.

The park’s design is typified by four parallel axial paths running east to west, each with its own distinctive character. The first, composed of large planting beds with singular Italian Stone Pines (Pinus pinea) in each, feels cooler — the lake, even now emptied of water for longer than twelve years, lends a lingering sense of moisture. The second path extends the full length of the park. A wall runs parallel, perforated by small arched openings to the other paths, and is covered in Boston Ivy (Parthenocissus tricuspidata). A row of Mediterranean Fan Palms (Chamaerops humilis) are silhouetted against this wall along it’s entire 400 m/1300 ft length. This surprisingly never feels monotonous; the varying texture of each palm, the backdrop of Parthenocissus, and the sporadic openings in the wall, bring a sense of movement and depth to the long path.

Passing through the arched openings in the second path’s wall, one reaches a series of more intimate spaces: a small amphitheatre, several groves of Atlas Cedar (Cedrus atlantica) with it’s characteristic blue foliage, and a paved path terminating in a small sports area.

The four east-west axial paths are intersected by a single north-south axis. One of the park’s most spectacular features marks the start of this secondary axis — the winter greenhouse. While greatly neglected, the structure appears stable and many of the glass panels remain, as do several of the subtropical plant species continuing to grow under its beautiful arched forms.

Another distinctive feature unique to the park is the row of pavilions that line the central east-west path. They form a beautifully repeating rhythm extending along the path, the faded pink cubes drawing your eye deeper into the park. Each is constructed of three thin columns and a fourth corner wall holding a bench planter that looks outwards through the wide openings. Above this planter is a skylight cut into the roof, providing some ambient light to the plantings.

Between the pavilions and along the perpendicular axis, what was once lawn now has a beautiful meadow quality in its overgrown state; and this, coupled with sporadic benches and groves of mature trees, lends a relaxed, informal, character.

The artificial hill (seen below with it’s ascending and descending staircases) was formed with the lake excavation soil and from earthquake and demolition debris. It rises at least 15 m/49 ft above the park, an impressive feature in an otherwise completely flat neighborhood.

At the base of the large hill lies the now-empty lake, drained in 2013 and left dry in the 12 years since. Puddles of rainwater still catch the light, helping to retain some of it’s reflective quality, as well as providing some feeding opportunities for birds. Yet the view of Mount Vesuvius, no matter what the context, is always captivating.

Park 2: Parco Fratelli de Filippo

Ponticelli, Naples, Italy

12.2 hectares / 30.1 acres

Opened the same year as Parco Massimo Troisi, and almost the exact size, Parco Fratelli de Filippo was inaugurated on June 30, 1995. At both Parco Massimo Troisi and Parco Fratelli de Filippo (pictured below), years of severe neglect have led at times to unsafe conditions in both parks. As a response, the city has permanently closed all entrances but one. At Parco Troisi, this meant a reduction from five entrances to one, and at Fratelli de Filippo, a reduction from eight to one.

To enter this single entrance at Parco Fratelli de Filippo, one crosses a jogging path that encircles the 1.5 km of park perimeter, often bustling with runners and walkers, and then enters through a corner bar. This bar is called “C’est La Ville Cafè”, a play on words with Villa Comunale, the term for the main public park of a district. When I visited on a Sunday morning in September, the café was crowded with people having animated conversations over coffee.

From the coffee bar entrance, one walks into the arcaded walkway that forms a square around the central plaza. This creates a shaded pathway for strolling, with views of the various planting beds and trees across the plaza. Immediately upon entering, I noticed there was a different social quality present in this park. Where there was a very subtle air of suspicion from passersby at Parco Troisi, here something felt different, more open and more social.

“Lei sa cosa stanno costruendo qui?” — Do you know what they’re building here? — the elderly man asked me, pointing towards a corner construction.

“Mmh…Forse un bagno?” — Hmm..maybe a bathroom? — I guessed.

“Ah, sarebbe bello. Menomale!” — That’d be nice, thank goodness! — He reached out to shake my hand, smiling warmly as he continued on his way.

At the east end of the plaza, a similar arcaded path emanates outward to the center of the park. Above the doorway: “Orto Urbano.” Orto in Italian refers to a garden specializing in edible plants and vegetables. On either side of this stepped walkway, community garden beds radiate outward. These are loosely divided by low, informal, wooden fences, and small footpaths of dirt or grass between the fences. Scattered groves of Stone Pine add to the dynamism of the space and create a dappled shade, and the low red roofs of the arcaded walkway form a domestic-scale frame to the wildness of the garden plots.

At the end of the arcaded path, the roof stops, and the sides of the walkway transform to large imposing concrete planters rising up a large constructed hill. The planters, approximately 1.2 m / 4ft tall, create an immersive effect to the path.

At regular openings in the concrete planters, curved concrete terraces radiate in concentric circles, each split into several community garden beds, much larger than the typical American plot. A few larger side paths and smaller, simple footpaths snake along the beds, and this gradient of pathways allows you to explore the gardens without feeling you’re trampling over someone’s plot.

As I was walking along one of these paths, a man working in his garden called out to me. As we approached each other, he eyed me suspiciously.

“Posso aiutarla?” — Can I help you? — he asked.

“Sono un giardiniere e paesaggista, sto solo esplorando il parco.” — I’m a gardener and landscape designer, just exploring the park —

I responded. His body language completely relaxed and he eagerly told me that I should go down and speak with the caretaker,

“Sta sempre llà, vicino al cancello” — He’s always there by the front gate — to sign up on the waitlist for a garden plot.

Continuing up the central path, the concrete planters end and open into a large circular lawn area. Immediately I felt the tone shift from the more social, working-farm part of the garden, to a quieter energy. This lawn was encircled by a concrete and metal pergola covered in Wisteria and built-in concrete benches, beautifully following the curve of the circle. In the center of the lawn circle lay a central stage for outdoor music, theatre, and children’s events, and wood bleacher seating framing one side.

I visited in early September, at the tail end of the summer holiday period, and I imagine the pergola and stage circle were a bit more unkempt than they usually are in periods of the year when the heat is less sweltering. But it was a truly special spot in the park.

Park 3: Parco Ciro Esposito

Scampia, Naples, Italy

14 hectares / 34.6 acres

I was reluctant to include Parco Ciro Esposito in Scampia as the third park of this study, as, in the past 10-20 years, the neighborhood has become a destination for architecture students to gaze upon and photograph in an exploitative manner — “disaster tourism.” Scampia is infamous for Le Vele, or The Sails, a series of now-condemned and partially demolished housing towers known for their extreme neglect, history of Camorra control, and open-air drug markets, brought to international ‘fame’ through the investigations of Roberto Saviano in his 2006 book Gomorrah, and the subsequent film and series of the same name.

I am glad I went, as it is a very moving space, not least for one key feature: the sheer expanse of the park combined with the raised walls/bastions that enclose it and give it the quality of a sunken garden.

Parco Ciro Esposito was designed by the architect Giulio Fioravanti starting in 1986, with landscape consultants Ippolito Pizzetti, Domenico De Liguori, Andreola Vettori, Carlo Bruschi, and Valeria De Folly d'Auris, and opened to the public in 1994. The park has been closed to the public since 2022, and is in a state of deep disrepair and neglect as plans for renovations are underway, but the raised walkways that line the north and part of the south side of the park are still accessible, and provide beautiful views into the park.

This raised walkway extends along the entire north side of the park, connecting with the main entrance pavilion, and bridging over four additional entrances that proceed into the park through the perimeter wall. These entrances meet the park at 45-degree angles, and the adjacent street, Viale della Resistenza, has been laid out to accommodate this angle in its crosswalks and to slow traffic.

The northern walkway is coupled with a long line of mature Camphor trees (Cinnamomum camphora). The lush, chartreuse green of the leaves, the dappled sunlight, and the remnants of the yellow painted metal of the bridge railings, all work together to create a feeling of brightness to this edge of the park. The large tree canopies also create a feeling of enclosure and sheltering, which dynamically contrasts with the expansive views of the park one looks out to over the parapet railing.

At two points on the walkway, the path opens wider to the south of the tree-lined path, the walls capturing some of the park space, and a recent small community orto project is underway.

These walls, that the perimeter walkway sits atop, drop down approximately 5m / 16ft to the park below. This sunken quality makes the park look otherworldly - there is something about the effect of the walls behind the loose naturalistic layout of trees that completely changes the energy of the space. In an open landscape without walls, the composition of mixed tree species plus lawn could imply an American suburban park, but instead, the backdrop of the walls frames everything and grounds it, adding a sense of tranquility. And even when you can’t see the walls clearly behind the trees and foliage, such as in these bottom two photos, there is still a subtle feeling of enclosure.

The elevated walkways bridge over the entrance paths that cross underneath. Similarly, these entrance paths create bridges over small canals along the bastion walls (currently drained and dry). The entrance gates have also been closed and neglected for the past three years, but these archways, like the rest of the park, could be very beautiful.

The central section of the park is defined by a linear plaza stretching 330 m / 1082 ft by 15 m / 49ft wide. This space is bookended by two large pergolas that span over it, each covered with overzealous Wisteria. A large sculpture feature sits centered between the two pergolas, and centered on the front entrance. Smaller paths emanating from the entrance bridges connect to this central space, and are mirrored symmetrically to the southern side, to entrances on the south side that are now defunct and overgrown. Most of the paths, and even the central linear plaza, are difficult to make out currently with the level of overgrowth.

The park previously had two lake features, one on either end of the east-west axis. Both have been empty of water for over 20 years, save a brief period in 2023. At the eastern lake, which meets the large earthwork hill and fountain, two islands and bridged walkways jut into the lake. These are covered structures with plantings and seating, and one can imagine that with the lake filled with water, it would be quite a special experience sitting there.

Conclusion: Top-down vs. Grass-Roots

The scale, intensity of intervention, and the quality of design in these three parks showed a newfound dedication of funds and talent to the city’s underserved areas. These three were inaugurated in the 1990s during the famous “Bassolino era” – named for Antonio Bassolino, the first mayor of Naples elected by popular vote rather than by city council. Bassolino entered office at the explosive time of the Tangentopoli crisis in Italy. This period of the early 1990’s, also called Mani Pulite, or Clean Hands, saw hundreds, maybe thousands, of corruption investigations: a cleansing fire that swept across the country, exposing corruption in every level of government, from major city halls to rural town councils, and leading to the dissolution of the two major political parties that had dominated politics in Italy since 1945 - the Christian Democracy and the Italian Socialist Party. In contrast, Bassolino represented a new generation, a clean slate from the corruption that had plagued Naples and the country as a whole.

Bassolino advanced a strong green agenda with the inauguration of these new parks and with urban design initiatives such as the removal of cars in Piazza del Plebiscito, the 2.5 hectare / 6 acre public square that had been turned into a giant parking lot in 1963.

Yet what is simultaneously shocking about these three parks, as well as our introductory Parco Ventaglieri, is that, while they were opened and inaugurated during the Bassolino era (two in 1995, one in 1994), they had already been completed in the late 1980’s, sitting gated, locked, and neglected for years. The PSER program began in 1981, and all of these parks started the design and construction process soon after. But the advent of the Tangentopoli period’s close scrutiny of politicians created what would come to be known in government chambers and the press as “paura di firmare”, or fear to sign, where politicians didn’t want to attach their names to major projects or expenditures in fear that it would cause them to be investigated. And so instead, in our case, all of these major park projects, which had indeed involved huge expenditure of government sums, sat shuttered and without maintenance for years.

Parco Ventaglieri, for example, was officially “completed” in 1992, but was left fenced and vacant. In this state, it quickly became a site for drug-dealing, drug-use, and other various criminal activity. It only “opened” in 1995, when 25 local residents occupied an adjacent vacant building, and created an organization to force open the park and manage it themselves. Over time, this Centro Sociale Autogestite DAMM (Diego Armando Maradona Montesanto) — Self-Managed Social Center ‘Diego Armando Maradona Montesanto’ — started daycare and after-school programs, an anti-violence ‘helpdesk’/support group for women in the neighborhood, a community gym, and many workshops held in the park.

Parco Fratelli de Filippo has also had periods of extreme neglect and repeated closures by the city, but has been saved by it’s energetic mobilization of community involvement over the past twenty years. The community gardens shown in my photos were not part of the original design, but created in 2015, spearheaded by the group Lilliput, an organization and day center for residents with substance dependance and dealing with social marginalization. The Lilliput Day Center, seeking to enable it’s patients to have freedom from the facility and to integrate more in the community, was able to obtain management of the park land from the City and began transforming what were completely abandoned, buried terraces into what exists now - the incredible community garden plots. Lilliput brought additional organizations, churches, and schools into the project, and local residents started wanting to be involved as well. By 2019, 400 local residents were involved in caring for and cultivating the garden plots. And in 2023, another organization - Era Cooperativa Sociale - started the Agro Living Lab Ponticelli with several other partner organizations, expanding and improving 8000 sq m / 2 acres of additional garden space in the park, and creating the outdoor theatre stage and seating.

Parco Ciro Esposito has also had very strong public advocacy and initiative-creation to transform and make the park healthy and safe. But the struggle against abandonment and neglect continues. All three of these parks - Troisi, Fratelli de Filippo, and Ciro Esposito, have active government plans for renovation and restoration of the parks, yet this, sadly, often spells further abandonment. There is a well-defined pattern of abandonment via restoration, where a large, well-funded, renovation project is announced, and then the park is fenced off and sits for years while the planning process is underway, and the structures and plantings are left without even a modicum of maintenance, deteriorating to a worse state than before the restoration was announced. This effect is currently evident at Parco Ciro Esposito, closed to the public for 6 years from 2008-2015 and again now since 2022, with plans of restoration, but in the meantime left to decay and overgrow. In January 2025 it was announced that the expenditure for the park renovations would be dropped from €780,000 to €400,000. With the neglect and closure of the park since announcing this restoration, the park conditions have greatly deteriorated, and yet now the budget for renovation is almost halved. And it is a painful echo for this neighborhood, where budget cuts during construction of the Vele towers led to the cutting from the project of many facilities and services, and these cuts are seen as a major factor in the exacerbation of the degradation of the housing and neighborhood.

Government-led, top-down design can create sweeping changes to neighborhoods and cities, such as the initial funding and coordination to create these parks. Yet the real life, success, and longevity of the projects comes from citizens themselves, from community engagement and community creation. I continually wonder if the great sums that are somehow discovered for the initial design and construction of a major project, could somehow instead be appropriated, subverted, to fund a very simple initial intervention, and then spread over years to fund community garden training, community workshops, and even to employ many community members to work in the park and to lead these community initiatives, avoiding the weekend-warrior phenomenon that often leads to the fatigue of community-led interventions in parks.

I think of Pershing Square in downtown Los Angeles, and the frequency of competitions to tear it down, redesign, and rebuild it. While it is, if I am honest, an objectively horrid design as it stands now, what if only the simplest interventions could be undertaken, and the rest of that magical funding that somehow appears before major construction, could instead be used to really create a community connection to the space, to create citizen ownership and engagement with the space, to pay community members to work in and on the space. These three parks in Naples prove, that in eras of big project design, even the most beautifully and intensively designed spaces can fail, and fail repeatedly. It is only the community that engages with them that has the power to bring them forward into the future.

- Jonathan Froines

For photo credits, click below to expand.

All photos by the author, Jonathan Froines, except where noted below.

Photo credits

Photo 1

Bianca. “Parco Dei Ventaglieri.” Google Maps, May 2023.

maps.app.goo.gl/URurVuWgRyAErQQs9

Photo 4

Romano, Massimo. “Ventaglieri, scale mobili a singhiozzo: ‘Colpa dell'influenza.’”

Napoli Today, 21 Dec. 2020.

napolitoday.it/cronaca/scale-mobili-ventaglieri-napoli.html

Photos 5–7

Comune di Napoli. “I parchi della città – Municipalità 2 – Parco Ventaglieri.” Undated photos.

comune.napoli.it/.../IDPagina/13191

Photo 8

Nappi, Mattia Luigi. “Park of Ventaglieri zone, upper side, Naples.”

Wikimedia Commons, 6 Dec. 2022, 11:01:24.

commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parco_dei_Ventaglieri,_upper_side,_Napoli_01.jpg

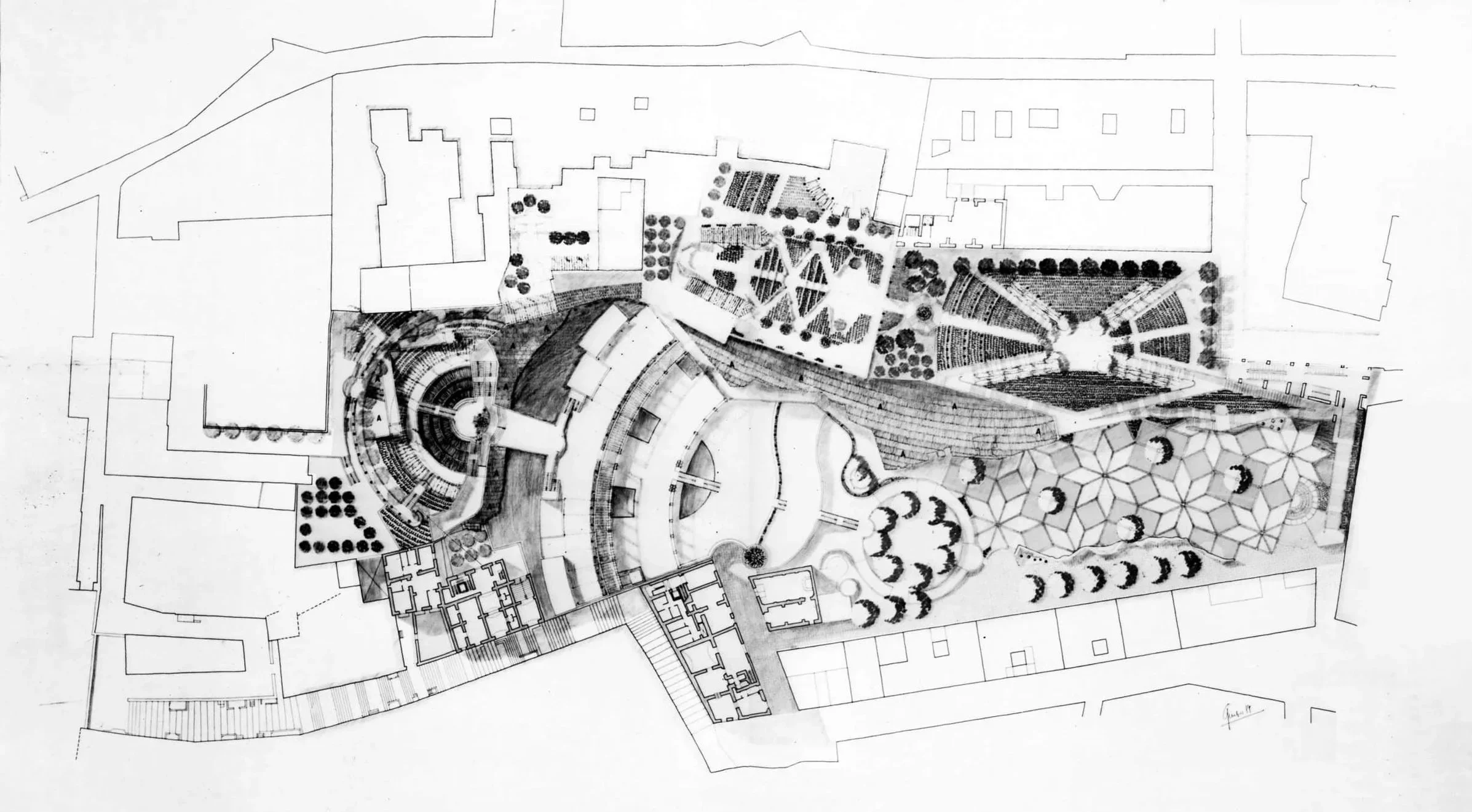

Image 11

Barbera, Lucio. “Parco Ventaglieri e Vico Avellino, Napoli - Tarsia - Planimetria.”

Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori di Roma e Provincia.

architettiroma.it/50_anni_professione/barbera-lucio/

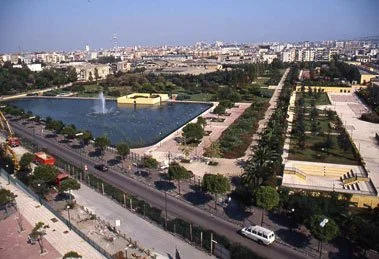

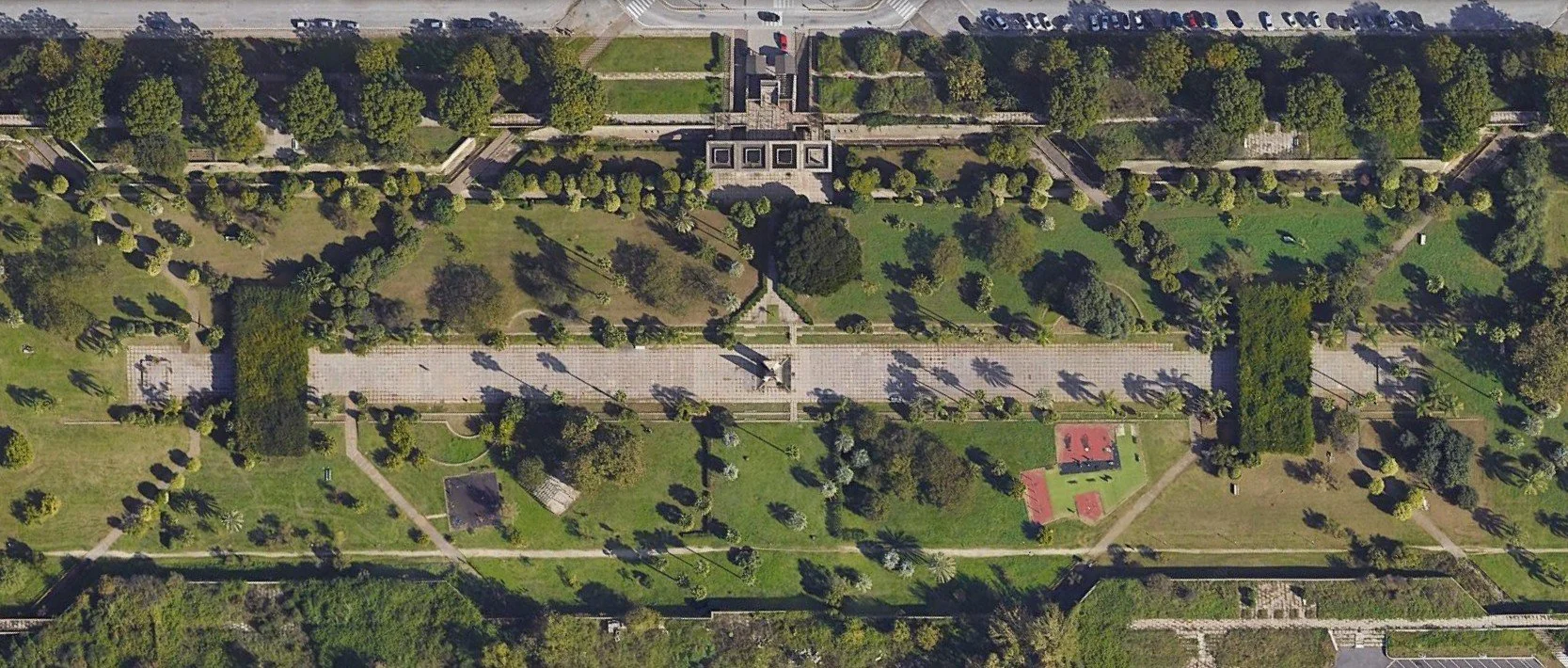

Image 12

Barbera, Lucio. “Parco Ventaglieri e Vico Avellino, Napoli - Tarsia - Vista aerea.”

Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori di Roma e Provincia.

architettiroma.it/50_anni_professione/barbera-lucio/

Photo 14

Palumbo, Giovanni. “Parco Troisi.” Comune di Napoli: Fotocittà 2009 – Parchi, Apr. 2009.

comune.napoli.it/.../GPI/2#GPContent

Photo 15

Palumbo, Giovanni. “Parco Troisi.” Comune di Napoli: Fotocittà 2009 – Parchi, Apr. 2009.

comune.napoli.it/.../GPI/3#GPContent

Photo 43

Siano, Ricardo. “Il sogno svanito del parco Troisi: ‘Riqualificate il polmone verde di Napoli est.’”

By Paolo Popoli. La Repubblica, 16 Feb. 2021.

napoli.repubblica.it/.../parco_troisi_ponticelli

Photos 44–46

Google Earth. “Parco Fratelli de Filippo, Napoli.” 2008, 2024. © Google 2025.

Photo 72

Studio Architetto Fioravanti. “Parco Centrale – Progetto.”

Progetti e Opere – Architettura.

studioarchitettofioravanti.it/.../progetto.html

Photo 73

Palumbo, Giovanni. “Parco di Scampia.” Comune di Napoli: Fotocittà 2009 – Parchi, Apr. 2009.

comune.napoli.it/.../GPI/6#GPContent

Photos 74–78

Google Earth. “Parco Ciro Esposito, Napoli.” 2024. © Google 2025.

Photo 85

Studio Architetto Fioravanti. “Parco Centrale – I Bastioni.”

Progetti e Opere – Architettura.

studioarchitettofioravanti.it/.../progetto_004.html

Photo 89

Studio Architetto Fioravanti. “Parco Centrale – I Materiali.”

Progetti e Opere – Architettura.

studioarchitettofioravanti.it/.../progetto_003.html

Photo 98

Google Earth. “Parco Ciro Esposito, Napoli.” 2024. © Google 2025.

Photo 101

Studio Architetto Fioravanti. “Parco Centrale – La Collina.”

Progetti e Opere – Architettura.

studioarchitettofioravanti.it/.../progetto_005.html

For full list of sources, click below to expand.

Bibliography

“Adotta uno spazio verde, una nuova area per l’Orto sociale di Ponticelli.” Napoli Città Solidale, 21 May 2021, Link.

Anteprima24. “Scampia, ira associazioni sui lavori del parco ‘Ciro Esposito’ Il Comune: ‘Le incontreremo.’” Anteprima24 Napoli, 9 Jan. 2025, Link.

Anteprima24. “Scampia, Parco Ciro Esposito: Le Associazioni di Quartiere Chiedono Risposte.” Anteprima24 Napoli, 10 Jan. 2025, Link.

“Barbera Lucio.” Ordine degli Architetti Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori di Roma e Provincia, n.d., Link.

Barbera, Lucio Valerio. “Due lezioni da un terremoto. 1 – Città estrema 2 – Il Borgo.” FAMagazine. Ricerche e progetti sull’architettura e la città, no. 55, 2021. DOI: 10.12838/fam/issn2039-0491/n55-2021/731. Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

Bassolino, Antonio. “Napoli, Il Sud e La «rivoluzione Comunale».” Meridiana, no. 26/27, 1996, pp. 203–46. JSTOR, Link.

Cederna, Antonio. “Mille case fatte, 7000 in cantiere.” la Repubblica, 23 Nov. 1984, p. 29. Link.

Cederna, Antonio. “Lo scudetto della ricostruzione. La Scandinavia? È in periferia tra Ponticelli e S. Giovanni.” La Repubblica, 20 May 1987, p. 19. (See scanned clipping via Comune di Napoli.) Link.

Cederna, Antonio. “Mia bella Napoli.” la Repubblica, 28 May 1994. (See digitized clipping via Archivio Cederna.)

Comune di Napoli. “Deliberazione n. 525: Intitolazione del Parco di Scampia a Ciro Esposito.” Comune di Napoli – Delibere di Giunta, 25 June 2017, Link.

Comune di Napoli. “Il verde a Napoli: I parchi della città.” Comune di Napoli, Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

Crudiezine. “Montesanto, 19 Anni di D.A.M.M. Maradona.” Crudiezine, 2 Sept. 2014, Link.

D’Avanzo, Giuseppe. “Bello e impossibile: Napoli, quel piano era un gioiello ma i partiti lo hanno abbandonato.” la Repubblica, 13 Dec. 1988. Link.

Del Monaco, Anna Irene. “Scuole di Scuola romana.” FAMagazine. Ricerche e progetti sull’architettura e la città, no. 56, 2021, pp. 64–80. DOI: 10.12838/fam/issn2039-0491/n56-2021/864. Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

Dines, Nicholas. “Urban Regeneration and the State: The Politics of Neighbourhood Renewal in Naples.” Quaderni di Sociologia, vol. 43, no. 21, 1999, pp. 77–99. University of Milano-Bicocca Open Archive, Link.

Il Mattino. “Villa comunale di Scampia chiusa e vandalizzata.” Il Mattino, 2011, Link.

Il Roma. “Nasce nel quartiere Ponticelli l’Orto urbano più grande d’Europa.” Il Roma, 21 May 2025, Link.

La Repubblica Napoli. “Riaperta la villa comunale di Scampia dopo anni di chiusura.” La Repubblica, 17 Nov. 2015, Link.

La Repubblica Napoli. “Scampia, lavori nella villa comunale, presto la riapertura del parco abbandonato.” La Repubblica, 21 Dec. 2012, Link.

Laino, Giovanni, and Daniela De Leo. Le politiche pubbliche per il quartiere Scampia a Napoli. Dipartimento di Urbanistica, Facoltà di Architettura, Università di Napoli Federico II, June 2002. ResearchGate, Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

“Napoli, l’agonia del Parco Troisi: ‘È tutto abbandonato.’” La Repubblica, 18 Dec. 2019, Link.

“Parco Centrale – Progetto.” Studio Architetto Fioravanti, Link.

Pastore, Antonio. “Napoli Ponticelli, finalmente il parco.” il manifesto, 2 July 1995, Link.

Schirru, Claudio. “Orto urbano a Napoli, 10mila mq nel Parco di Ponticelli.” Eco in Città, 21 June 2023, Link.

“Tavolo di gestione” (archived page). Parco Sociale Ventaglieri via Internet Archive Wayback Machine, 24 Sept. 2015 capture, Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

Tina, Pasquale. “La Villa comunale di Scampia diventa ‘Parco Ciro Esposito’.” la Repubblica (ed. Napoli), 24 June 2017, Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

“La villa comunale di Scampia è diventata ‘Parco Ciro Esposito’.” la Repubblica (ed. Napoli), 25 June 2017, Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.

“Un nuovo polmone verde per Ponticelli: inaugurate 50 terrazze all’interno dell’Orto Sociale Urbano del Parco De Filippo.” NapoliVillage, 18 June 2021, Link.

“Ventaglieri Social Park. Participation Changes Naples [Ventaglieri Social Park. Public Participation Changes Naples].” Participedia, last updated 12 Feb. 2020, Link. Accessed 9 Oct. 2025.